Easter: Presence and Absence

There is scriptural precedent for people feeling left behind by God. Job is, I think, the most famous, but Martha felt abandoned when Jesus did not come in time to save her brother. She went out to meet Him when he finally came, three days late, and said, “Lord, had you been here my brother would not have died.” In jail, Joseph Smith wrote, “How long shall thy hand be stayed?” On the cross, Jesus cried out “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

What I think is interesting about all of these moments of rebuke by the servant to the master is that, while they are cried out in agony of soul, in hurt and anger, perhaps in feelings of betrayal, they are also always expressions of faith. Martha is hurt that Jesus did not come to rescue her brother—because she knows that if he had, he could have stopped death. This was Martha’s faith, that the Lord she worshipped had power over death. Joseph Smith wrote in the pain of his own suffering and the suffering of those who followed him. He had witnessed death and illness and imprisonment and rape, and he knew that His God had power over all of those things and all who perpetuated them. And, on the cross, Jesus knew that His Father could save Him, could be with Him, could preserve Him. All of these people would have done anything to feel God with them, and what God seemed to require that they do was, for a time, feel alone.

These were people who knew God and believed in His power and didn’t understand why He wasn’t intervening on their behalf as He had at other times. When we feel abandoned by God, it is because we have felt His presence before.

I think about this a lot, because when I was nineteen God stopped talking to me and, suddenly, I was aware of how present He’d been.

Nineteen was when it was time to decide if I was going on a mission for my church. All my friends were going. All my roommates were packing their bags. Most of the women my age I was casually acquainted with were making covenants in our temple and buying the drab clothes they required sister missionaries to wear in those days. The church had recently pushed the age change for women down from twenty-one to nineteen, and the excitement was palpable. You could walk around Brigham Young University’s campus, and it was in the air: people were getting their papers in (officially indicating to the church that they wanted to go), were wondering about where they would go, when they would go, hoping their boyfriends would wait for them.

It was a mass exodus, and I was standing in Egypt waving a handkerchief after them. I wasn’t going. I didn’t want to go.

I’ve tried to puzzle this out over the years—why did I not want to go? In many ways, it seems very much like my thing. I’m still not sure, though I’ve found fragments of reasons, some good and some bad. Certainly I was scared of the homesickness I would feel when I could not just pick up the phone and call my family. More than that, though, I was still figuring out my version of universalism and how that might line up with missionary work, and I was still very much working through religion’s connection with colonialism. I’m not one for fast processing, and I’m still figuring some of this out. I was not going to work through it before it was time for me to serve. All of that was fine, and the intense social pressure to go was even fine, because I have always been intensely obstinate in the face of social pressure (see: all the terrible things I wore in high school as rebellion against the patriarchy).

The thing that wasn’t fine was that God wasn’t talking to me or, at least, that I couldn’t hear him. I was trying. My prayer at the time was, “Father, I don’t want to do this, but I’ll do it if you want me to. You know that’s the deal between us, and I’ll keep the deal.” I prayed it, and I meant it. I didn’t want to go, but more than not wanting to go I wanted to serve God. If a mission is where He needed me, then that’s where I’d go. But the only thing I got back from God was some version of a cosmic shrug. Like, “Whatever.”

Karl Rahner explains this feeling better than anyone I’ve ever encountered. He says, “When I pray, it’s as if my words have disappeared down some deep, dark well, from which no echo ever comes back to reassure me that they have struck the ground of Your heart."

Rahner and I, it wasn’t that we stopped believing in God, we stopped feeling Him with us.

I think the apostles may have felt this way after Jesus’s death. They had “hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel” (Luke 24:21), and then he died. They watched it, and they must have felt the searing pain of seeing their friend and Lord suffer, but perhaps they also felt mislead. They had followed, they came and they saw as he asked, and now he was leaving them. They had warned him that coming to Jerusalem was dangerous, and now he forsook them in the middle of that danger.

And they knew—they knew the same way Martha did—that their Lord had power over life and death. Why wasn’t he using it to protect himself and them?

This is the part of the Easter story that the Holy Week is so good at telling. We have the last part of the week to remember the pain of believing that God was gone, that the Lord you worshipped had died. On Tenebrae, services are held in which the lights are slowly extinguished. In some services, the last light to go out is the Christ candle, carried out of the sanctuary, until everyone is sitting in darkness together, as Jesus’s followers were after his death. A loud noise at the end of the service represents the closing of the tomb, and the congregation files out of the dark chapel in silence, remembering those who lived through the hopelessness of believing that their God died.

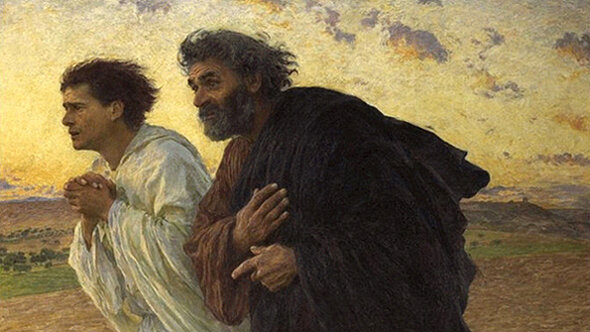

J. Kirk Richards, “Why Weepest Thou”

In this context, it makes sense to me that when the women rushed from the empty tomb to tell the male disciples that the Lord was not there, that he was risen, the male disciples dismissed them. I think they might have been angry, and I think they were angry because they were afraid. They couldn’t believe again, because if they believed and it wasn’t true, their hearts would break.

For those disciples, the empty tomb meant only emptiness. It meant that their Lord was absent, gone, again.

But the hope (one of the hopes) of the Easter story is that the absence of God is never an indication of abandonment, but is always a testament to a larger presence. Jesus was not in the tomb because he was risen, because he truly had conquered death. Absence did not mean absence, it meant presence, it meant God. Jesus was not in the tomb because he was in heaven. He was everywhere.

After days of agony, Jesus was suddenly among them again, walking with them, eating with them, teasing them, blessing them and giving them power. And then he was gone again, back up to heaven, but the disciples knew what they hadn’t before, that the Lord’s absence was not absence. They knew he was with them wherever they went.

In my much smaller scale rendition of this drama, God came back to me at three o’clock in the morning as I knelt in agony in my living room after months of prayers that didn’t stick. “Don’t you care?” I asked Him, putting all my hurts in front of Him. “Don’t you care?” I asked over and over.

And—stronger than almost any impression I’ve ever received—the answer came back, Do you think you are so broken that I cannot fix you? Of course I care.

Though I’ve had many continual small scale interactions with God in my life, this one was different. He’d been gone, and he came rushing back. God is usually like a good well for me—easy to draw on. This time, though, He was a flash flood God. He didn’t tell me what to do, because God almost never tells me what to do, but He let me know that He was there, that He was paying attention and had been the whole time. He didn’t tell me what to do, but He was back, and we figured it out together.

I needed that answer then, to be able to climb up off the floor and go to bed, feeling my God with me, but I would need it more later. As I climbed into realities much more difficult than the one I lived in then, I would need to know over and over that I was never so broken that God could not fix me, that even when I cannot feel Him, He is there.

I have had a hard time talking to God the last few weeks. It’s gotten better over time, but still when I kneel to pray, I cannot always find Him. This may be upheaval—nothing in my life is where it was last month. In the last few weeks my school was cancelled, and I temporarily moved home to my parent’s house, hauling half a week of clothes, a semester’s worth of books, and a brand new husband. Right now I am haunted by small things, like my plants slowly dying in my empty apartment. I am haunted by enormous things, like the mortality of everyone I love.

Much like when I was nineteen, I desperately want to have the kind of access to God that I’m used to, and I’m struggling to find it. I still don’t know why God withdraws when He does. I don’t know why He wouldn’t talk to me when I was nineteen. I don’t fully understand why He required Lazarus’s death or Jesus’s suffering. But I remember now, as the apostles must have, that when I am seeking God and cannot find Him, His absence is an empty tomb—always a sign of something larger at work, of Godly presence so pervasive, I cannot yet see it.

“The Disciples Peter and John Running to the Sepulchre on the Morning of the Resurrection” by Eugène Burnand